Report from the Food Standards Agency Allergenicity Workshop held 28th February 2024

On this page

Skip the menu of subheadings on this page.Summary

The Advisory Committee for Novel Foods and Processes (ACNFP) previously highlighted the need for the FSA to consider revising and updating the guidelines for assessing novel foods (including GM foods and PBOs), specifically for developing a clearer framework for the allergenicity risk assessment process. This was in response to the evolving science of food allergenicity and recent applications seeking authorisation as novel alternative proteins.

This FSA Allergenicity Workshop, held in person in February 2024, brought together food allergy experts from a range of perspectives to gather their viewpoints on the current and future approaches for allergenicity risk assessment. Three topic areas were considered: Allergen Bioinformatics; In vitro approaches; Exposure and Thresholds. Participants were invited to take part in a round table discussion to review the findings of the workshop and make recommendations to the FSA.

Based on these discussions, and other supporting sources of information (FAO publications; EFSA reports; published peer review papers) a draft workflow was developed. This template will be used as a starting point to revise the guidelines for the novel food allergenicity risk assessment.

1. Introduction

1. New and alternative proteins from a range of sources are expected to enter the UK market in the next few years. These include cell cultivated meat, insects, and extracts of common foods such as legumes, seaweed, and grasses. For these foods to be successfully scrutinised by the FSA and FSS before being placed on the market, applicants to the novel food process would be aided by guidance on the data needed for assessment, assessors need a clearer structure for evaluating these products, and clinicians and consumers need to have confidence in the safety assessment of these novel foods.

2. The Advisory Committee for Novel Foods and Processes (ACNFP) had previously emphasised the need to consider the issue of the potential allergenicity to consumers and the evolving science in this area. During the review of recent dossiers on novel alternative proteins, the Committee highlighted the need for further research, and in many cases, evidence to reduce uncertainties in the allergy risk assessments. Members recognised that the science of food-related allergy is relatively new and evolving worldwide, and there may inevitably be knowledge gaps and residual uncertainties in allergy risk assessments. The potential for revised guidance based on the evolving science of food allergenicity and the development of a clearer framework for review was considered a high priority by the ACNFP to support their work in reviewing innovative products.

3. The FSA Allergenicity Workshop brought together relevant experts from a range of perspectives to gather their viewpoints on the current and future approaches in allergenicity risk assessment. This output summarises their discussions and forms the basis of the proposed recommendations that the ACNFP will provide to the FSA. The report covers Type 1 food allergies via the oral route only and does not concern skin allergy via contact with food, including small molecules in a Type IV allergy, e.g., from citrus fruit or plant handling, etc.

4. The proposals will be used by the FSA to define the data requirements from industry more clearly, so that consumers, clinicians, and regulators can be confident that the outcome of the novel food assessment on allergenicity is appropriate, relevant and proportionate.

2. What are we trying to anticipate for a novel food via an allergenicity risk assessment

5. The aims of the allergenicity assessment are not clearly defined in the current guidance. However, in conducting the allergenicity risk assessment of a novel food, this evaluation attempts to explore the following areas.

6. Determining the potential for cross-reactivity to a protein present in a novel food in those consumers who have a pre-existing clinically relevant allergy to another protein or food ingredient. The exposure to the novel protein could cause cross-reactive severe allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis, and even death. This can be illustrated in a case study concerning anaphylaxis following consumption of crocodile meat for the first time. The patient had an existing clinically relevant allergy to chicken meat; however, further analysis revealed extensive sequence homology between chicken and crocodile α-parvalbumins (Ballardini et al., 2017).

- Cross-reactivity occurs when a protein in one food is mistakenly recognised by the immune system as another protein due to similar structural features present in both proteins. Certain groups of foods allergens, such as tree nuts, are associated with high rates of clinical cross-reactivity (Francis et al., 2020). For example, allergenic responses following consumption of pecans are notable in consumers with a clinically relevant allergy to walnuts (Brough et al., 2020).

7. Determining the potential for de novo sensitisation and the development of a new clinically relevant food allergy in consumers of a novel food that has not been seen before. This is extremely challenging to predict.

- The allergenicity risk assessment already considers the cross-reactivity of a protein from a novel food with known food allergens. By contrast, de novo sensitisation to novel allergens, with the current science, can only occur be identified retrospectively. There are no animal models or in vitro models that can be used to predict whether a de novo sensitiser will appear on the market from a novel food.

8. Consider the apparent changes in the symptoms of clinically relevant allergenic responses reported by consumers over time.

- There is a recognition that there are underlying genetic, immunological and environmental factors which play a key role in Type I allergy or IgE-dependent reactions, including food allergy (Falcon and Caoili, 2023). Whilst food allergies to crustaceans, fish and tree nuts appear to be life-long for most allergic individuals (Luyt et al., 2014), around 80 – 95 % of children could outgrow allergies to cow’s milk proteins, eggs, soy and wheat flour by the age of five according to Sicherer and Sampson (2014).

9. Assess the evidence concerning the population exposure levels for allergenic proteins and the scope of reactions observed in consumers with clinically relevant food allergies. From this information, estimate the scale of food allergy in the UK population, and where possible, predict the likelihood of a clinically relevant allergenic response for a similar novel protein.

- The Patterns and Prevalence of Adult Food Allergy (PAFA) report found that around 6 % of the UK adult population are estimated to have a clinically confirmed food allergy (University of Manchester et al., 2024). Peanuts (legume) and tree nuts were most likely to cause an allergic reaction. Fresh fruit, such as apple, peach and kiwi fruit were also notable as allergenic foods (fruits are associated with allergies to birch pollen, also known as pollen-food allergy syndrome). Allergies to milk, fish, shrimp and mussels were reported to be uncommon in the UK.

- The prevalence of allergy in Europe is expected to be different compared to the UK. The European Community Respiratory Health Survey II (ECRHSII) study reported a wide range in the prevalence of sensitisation (i.e. production of specific IgE) to food allergens, ranging from 7.7% in Iceland to 24.6% in the USA (Knox et al., 2003). The EuroPrevall study reported that the prevalence of probable IgE-mediated food allergy (i.e. reported reactions to a food consistent with an IgE-mediated food allergy and evidence of sensitisation to that same food), ranged from 0.3% in Athens and up to 5.6% in Zurich (Lyons et al., 2019).

- The PAFA report also noted that childhood food allergies persisted into early adulthood. In addition, a significant number of adults reported that their food allergies developed in adulthood, which suggests that the burden of food allergy can increase with age and sensitisation phases, with multiple exposures, could progress during childhood and adolescent years.

3. Background to Current Allergenicity Risk Assessment Approaches

10. The current allergenicity risk assessment strategies in the Guidance on the preparation and submission of an application for authorisation of a novel food in the context of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 are based on the principles and guidelines of the Codex Alimentarius for the safety assessment of foods derived from ‘modern’ biotechnology (FAO/WHO, 2001).

11. In 2006, the EFSA Panel of Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO Panel) first published the “Risk assessment of genetically modified plants and derived food and feed” (EFSA GMO Panel, 2006). This guidance has been periodically updated in response to scientific and technological developments in this field.

12. In 2017, a Working Group from the EFSA GMO Panel was tasked with developing supplementary guidance for the allergenicity assessment of genetically modified (GM) plants (EFSA GMO Panel, 2017). The resulting publication addressed three main topics:

(i) non IgE-mediated adverse immune reactions to food (coeliac disease).

(ii) in vitro protein digestibility tests.

(iii) endogenous allergenicity (where the genetic modification results in untended changes to the levels of endogenous allergens that may adversely affect human and animal health).

13. The GMO Panel reviewed the scientific and regulatory developments in each of these areas and then considered how these approaches could be implemented into the risk assessment of GM plants. Recommendations were made to supplement the previous guidance documents for points (i) and (iii). In the case of in vitro protein digestibility tests, the GMO Panel indicated that further research was needed before additional guidance could be provided (EFSA GMO Panel, 2017).

14. The EFSA GMO Panel have since updated their advice concerning in vitro protein digestibility tests in allergenicity and protein safety assessments (EFSA, 2021a). The Panel concluded that there was a need for more reliable systems to predict the fate of the proteins in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Also, further work was needed to fully understand the complexity of digestion and absorption of dietary protein and develop approaches so that this information can be integrated into a weight-of-evidence approach.

15. In June 2021, the Allergenicity Working Group of the EFSA GMO Panel organised an online workshop on allergenicity risk assessment (EFSA GMO Panel, 2021b) which considered issues relating to IgE cross-reactivity and de novo sensitisation prediction. These topics had not been addressed by the GMO Panel in their 2017 publication. The information gathered from the workshop was used to guide the drafting of a Scientific Opinion on the current gaps and future development needs for allergenicity and protein safety assessment (EFSA GMO Panel, 2022).

16. Based on the prior experience gained by risk assessors, and new developments in the field, there was a recognition that certain key aspects of food allergenicity assessment needed to be updated. These were identified as:

(i) better standardisation on the use of the available knowledge on the source of the gene and the protein itself – context of clinical relevance, route of exposure and potential threshold values of food allergens.

(ii) modernisation of in silico tools used with more targeted databases.

(iii) better integration of in vitro testing, with clear guidance on how protein stability and digestion inform the assessment and on the use of human sera.

(iv) better clarity on the use of the overall weight-of-evidence approaches for protein safety and the aspects needed for expert judgement.

17. The FAO/WHO recently published their reports on the risk assessment of food allergens. Part 1 reviewed and validated the Codex Alimentarius priority allergen list through risk assessment (FAO/WHO, 2022a). Part 2 reviewed and established threshold levels in foods for the priority allergens (FAO/WHO, 2022b).

18. Part 1 included a review of the criteria for exempting foods that are on the priority allergen list from labelling (FAO/WHO, 2022a). The following considerations were identified:

(i) is the level of protein likely to cause a reaction (above threshold value)?

(ii) is the type of protein likely to cause a reaction (not all protein in food may be allergenic)?

(iii) does the production process reduce the potential allergenicity of the food?

(iv) is there an absence of a clinical/biological reactivity in affected individuals?

(v) is the food derivative well-characterised and specified?

19. According to the current EFSA guidance (EFSA NDA Panel, 2016), the appropriate methods for investigating the potential allergenicity of foods include the following:

Protein analysis

- Protein content in the novel food,

- Molecular weight of the potentially allergenic protein, heat stability, sensitivity to pH, digestibility by gastrointestinal proteases,

- Degree of sequence homology with known allergens,

- Immunological tests (e.g. western blotting).

Human testing

- Detection of specific IgE antibodies,

- Skin prick testing,

- Double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge studies.

20. In February 2024, EFSA published a consultation document for the proposed revision of the Guidance on the preparation and submission of an application for authorisation of a novel food in the context of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. This includes an updated section on the assessment of the allergenicity of novel foods which recognises four classes of novel foods.

21. A summary of the proposed information requirements is shown in Table 1 below:

Table 1: Proposed data requirements for the allergenicity assessment of novel foods taken from EFSA public consultation document (February 2024).

|

Class of Novel Food |

Suggested data requirements |

|

Novel foods with no protein derived from the production process. |

No allergenicity-specific data requirements. |

|

Novel foods derived from allergenic foods subject to mandatory allergen labelling. |

Quantify the presence of the known allergen(s) in the novel food. |

|

Novel foods derived from allergenic foods not subject to mandatory allergen labelling. |

Prevalence of food allergy. Type and severity of symptoms. Potency of allergenic food. Known clinically relevant allergens in source of novel food. Detection, identification, and quantification of allergenic proteins in novel food. |

|

Novel foods for which the allergenic potential is unknown.*

|

Literature search on novel food, its source, and closely related species. Identification and characterisation of protein. Allergenicity assessment. |

* Novel foods for which the allergenic potential is unknown is sub-divided into single protein or simple protein mixtures, and complex protein mixtures or whole foods. This distinction recognises the fact that the current allergenicity assessment approach was designed for single proteins rather than complex mixtures. The proposed revised guidance document indicates that more information would therefore be expected with increased complexity compared to single proteins or simple protein mixtures.

4. Developing an ACNFP view on Allergy Risk Assessment

22. The ACNFP is currently using the principles of the EFSA Guidance on the preparation and submission of an application for authorisation of a novel food in the context of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 (EFSA NDA Panel, 2016), as the basis for allergenicity risk assessment. These guidelines incorporate the key principles from the allergenicity risk assessment of GMO products used as food or feed. This guidance recognises that “food allergens are mostly protein” and the basis for allergenicity assessment is “the default assumption for novel foods containing proteins is that they have allergenic potential.”

23. Since 2016, new considerations have emerged from EFSA and FAO in the past decade, therefore, it is timely to consider whether there should be changes to the guidance post-2016, hence the need for a workshop.

24. The aim of this workshop was to provide an overview of the state-of-the-art in the science of allergenicity risk assessment and to seek views on the needs of the risk assessment.

25. The workshop was divided into morning and afternoon sessions.

26. In the morning session, two presentations were made as an introduction for participants who were unfamiliar with the current allergenicity risk assessment process for novel foods:

- Context for the Allergenicity Risk Assessment for New Foods in the UK.

- Experience gained from the current EU Approach to the Assessment of Allergenicity for New Foods.

27. This was followed by question-and-answer sessions which were held after each talk.

28. Participants were then split into three groups and rotated through three breakout sessions:

- Breakout session 1: Allergen Bioinformatics

- Breakout session 2: In vitro approaches

- Breakout session 3: Exposure and Thresholds

29. Each group was asked to consider a series of topic related questions during each breakout session and provide feedback. The questions and an edited summary of the responses from these sessions are provided in Appendix 1.

30. In the afternoon session, a summary review from each breakout group session was followed by a round table session featuring all the participants. The participants were asked to consider how this information could be used to further develop the assessment of the potential allergenicity of novel foods.

31. The following is a summary of the key comments or questions raised after each presentation:

- Context for the Allergenicity Risk Assessment for New Foods in the UK.

32. The first presentation initially outlined the responsibilities of the FSA and FSS in the safety assessment of novel foods, including their potential allergenicity. The role of the ACNFP in the novel food regulatory process was also highlighted.

33. The reasons for reviewing the allergenicity assessment were then considered, with the key drivers being an increased interest in alternative proteins, the UK allergic population, and the opportunity to consider this issue in the UK since leaving the EU.

34. On this basis, the workshop provides the opportunity to bring together the current thinking on allergenicity assessment, ensure that we are making the best use of the available tools; communicate the approach to applicants, and lastly, look to the future and consider what might be next.

Question: Why are allergic responses in the UK population different from other parts of the world?

35. Food allergies are set apart from other toxicological concerns, as immune-mediated adverse effects can manifest following exposure to a substance due to a pre-disposition in the biology of some people in the population. This means that some people could react to an allergen, but many people would not suffer adverse reactions. Also, for allergens, the classical toxicology concept of the ‘dose makes the poison' does not hold. Sometimes very low intakes or allergens can lead to a serious allergic response in some pre-disposed consumers. Also, the science of the immunology of food allergenicity is not fully understood, making the outcome challenging to risk assess.

36. The observed allergic responses in the clinical setting are very heterogeneous. The UK has more people with food allergy and different patterns of allergy compared to Europe or the USA. For example, peanut is a common allergen in the UK (Stiefel et al., 2017), and Brazil nut consumption in the UK is linked to more allergic reactions compared to other parts of the world where it’s less commonly consumed (Weinberger and Sicherer, 2018). Hazelnut is a major allergen in Europe (Datema et al., 2015), and in Southern Europe, some fruits, e.g. peach (Puche et al., 2018), are major sources of allergens. The reasons for these differences are largely unknown.

Question: Is there a link between prevalence of food allergy and social deprivation in the UK?

37. The relationship between socio-economic status and food allergy in the UK is unclear. Previous studies have suffered from a number of key limitations, including insufficient representation of social and demographically diverse population groups, problems with cohort retention which can potentially increase bias, relatively small sample sizes, and relevant sociodemographic variables not reported (Warren and Bartell, 2024).

38. Published studies have noted a relatively greater increase in children diagnosed with peanut allergy over a 14‐year period (1990–2004) from non‐white backgrounds (Fox et al., 2019), significantly higher incidence of anaphylaxis amongst British South Asians compared with those from a White Caucasian background (Buka et al., 2020), and higher rate of food allergy in non‐white participants: 5.3% in those from a white background to 19.3% in Asian/black/Chinese participants (Perkin et al., 2016). Cultural norms and communication may be a factor, where adherence to advice is reportedly lower in those from a non‐white background (Perkin et al., 2019). This is a major knowledge gap because of the potential impact on access to health care, which is important in terms of dietary advice and risk avoidance (Turner et al., 2021).

- Experience gained from the current EU Approach to the Assessment of Allergenicity for New Foods.

39. The second presentation began by providing an overview of the EU approach to the allergenicity assessment at the time of the workshop in February 2024. Key points included the assumption that any protein present may be allergenic, and the focus of the assessment concerns the cross-reactivity with known food allergens and not de novo sensitisation. However, it was noted that applicants were unclear when further analysis or investigation was warranted because there was no tiering of the data requirements. Also, applicants needed to cross reference with other EFSA publications during the allergenicity assessment.

40. A review of the data requirements in the guidance was discussed, along with a review of two previous UK novel food applications – chia seeds (risks managers advised precautionary labelling based on allergenicity assessment) and bee venom in honey (not authorised due to potential for serious allergic reactions).

41. Lastly, a summary of the UK experience of the allergenicity assessment under the EFSA guidance noted the following:

- New evidence and thinking emerging from the other areas of food allergy science provide a basis for considering the approach to the allergenicity of novel foods.

- Most applicants are not clear on what information they should provide.

- Characterising the allergenic risks sufficiently can be challenging.

- Ensuring the allergenicity assessment is proportionate can be difficult.

Question: What approaches should applicants use to conduct an allergenicity assessment?

42. The amount and source of the protein in the novel food are key indicators of potential allergenicity, especially if the new protein is similar to a protein already known to be an allergen. The potential allergenicity of a protein is assessed based on information concerning the characterisation of the protein (e.g., molecular weight, heat/pH stability, digestibility), the degree of sequence homology with known food allergens and immunological tests (e.g., Western blotting).

43. Further analysis using human subjects may be needed where bioinformatics indicates potential cross-reactivity with a known food allergen. This could involve sera testing, skin prick testing or placebo-controlled food challenge. These tests require prior ethical approval.

44. Specific IgE binding between the novel food and sera from individuals with a clinically relevant food allergy or positive skin prick tests both confirm IgE sensitisation. However, confirmation of a food allergy requires a positive result from a double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge, along with relevant history, symptoms and time of onset consistent with an IgE-mediated food allergy to a relevant food, and evidence of sensitisation to that food.

45. Applicants have difficulty deciding which data to provide or why this is needed. Typically, they assess the novel food for cross contamination by the fourteen major allergens (Annex II of assimilated Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011). They may conduct a bioinformatics analysis or a literature review, but then struggle with human testing trials, e.g., sample sizes.

46. This is an opportunity to challenge the status quo because it is not always proteins that cause allergy in consumers. There needs to be an awareness that non-proteins can also cause allergy. For example, alpha-gal syndrome causes food allergenic symptoms after the ingestion of meat, although this is currently the only known example of a non-protein producing a clinically relevant allergenic reaction in consumers. Some skin reactions can be elicited in food manufacturing contexts by handling low molecular weight chemicals in fruits or natural substances from flowers or colophony for example – but this skin allergy (Type IV b hypersensitivity reaction – see Jutel et al., 2023) was out of scope of this workshop.

47. There is also a recognition that the production process may impact on the potential allergenicity of a previously well-characterised protein glycosylation reactions can occur during prolonged storage or thermal processing. This may impact on the allergenicity of proteins by altering the structure of the epitope, revealing hidden epitopes, concealing linear epitopes, or creating new ones. These changes are difficult to predict because they depend on different factors (Xu et al., 2024).

48. Thermal processing can also alter the allergenic potential of known food allergens. For example, boiling can reduce the allergenicity of egg white (Cherkaoui et al., 2025), whereas scrambled egg white has minimal impact on the allergenicity (Gantulga et al., 2024). In baked foods, where egg as an ingredient, the composition of the food matrix can also impact on the allergenicity (Liu et al., 2024).

49. There is a need to be open to the fact that some of the science in the FAO/WHO Evaluation of Allergenicity of Genetically Modified Foods report (FAO/WHO, 2001) is no longer correct and changes need to be made. For example, to achieve a 95% confidence level that a major allergen is not present during serum screening, at least six samples of sera must be tested. Statistically, this number of samples would only provide a 54% confidence level.

Question: Should the allergenicity risk assessment investigate IgE-mediated allergic reactions only or also include de novo sensitisation?

50. The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) recently published a position paper which proposed nine different classes of hypersensitivity reaction (Jutel et al., 2023): Type I or IgE-dependent reactions occur in food allergy and include two distinct phases: a sensitisation phase and an effector phase. The other hypersensitivity reactions are mediated by antibodies IgG and IgM (Types II and III), cellular responses (Type IV a, b and c), tissue driven mechanisms (Types V and VI) or direct response to chemicals (Type VII). Predominantly, these other types of hypersensitivity reaction have no role in food allergy. The exception is Type IV b which overlaps with Type I at the final stage when IgE synthesis is triggered.

51. Other clinically relevant allergies resulting from exposure to food can be triggered by different pathways. Non IgE-mediated allergies, such as food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, can be serious (Zhang et al., 2021), but currently there are no biomarkers available. The PAFA report stated that around 1 % of the respondents have a medical diagnosis for coeliac disease (University of Manchester et al., 2024). This condition, along with IgE-mediated allergies, have validated biomarkers. Where there is evidence of sensitisation and elicitation, there is a potential to induce allergy to a food. However, investigating the de novo sensitisation potential and subsequent role in the development of a clinical food allergy is even more challenging than identifying whether a particular allergen is responsible for a reaction.

52. There should be a recognition that there are gaps in our knowledge and further research is needed. Currently, there are no scientific models to predict de novo sensitisation, e.g., from insects, that can be applied in a regulatory setting (Crevel et al., 2024). From a proportionality perspective, the current tools should be used to investigate the likelihood for a potential risk based on evidence that a substance has the potential to act as an allergen. Further, the risk to the population from consumption of a novel food should be considered. If fewer people are exposed to the food, in all probability, clinically relevant allergies may not manifest themselves. However, it cannot be ruled out that a few idiosyncratic responses could occur that would have been impossible to predict.

53. There is a need to be clearer with risk managers about the current state of the science.

Question: Should there be a role for post-market monitoring given the difficulty in predicting allergenicity?

54. It is recognised that this tool has not previously been used as a source of evidence for the prevalence of allergy but could be flagged as useful. A number of considerations would need to be addressed – How to collect this information? How to validate the quality of clinical data? How can potential bias (who responds and/or who is involved) be addressed? Should public information be included?

55. Research is taking place to consider the best approach for conducting post-market surveillance and how this data can be used to inform the allergenicity assessment. Examples include the UK Fatal Anaphylaxis Register, which is funded by the FSA, and the Monitoring the Safe Introduction of Novel foods (MoSIN) initiative, which is based in the Netherlands. The UK register is an important source of information on products because this could provide an early indicator for potential novel food allergy issues resulting from cross reactivity. This could also provide an indication where further review or research is needed to understand the trends seen. However, there is a recognition that funding for similar initiatives is limited.

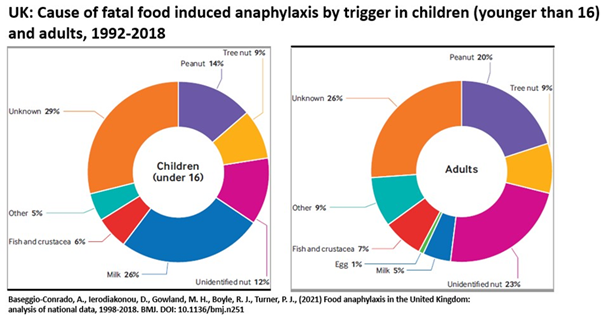

56. Post market surveillance of fatal reactions to food is currently not very effective, and of course, is too late to be protective of the consumer: 29% of reactions in children and 26% of reactions in adults were recorded as attributed to food allergy, based on timing, pattern of symptoms, etc, but the food was not identified.

57. Attributing reactions to novel foods or foods subject to novel processing methods is even more challenging. Novel foods are defined in assimilated Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 as foods that were not used for human consumption to a significant degree within the (European) Union or the UK before 15 May 1997. Therefore, a novel food could be a protein extract from a whole food already consumed in the diet. A lack of clinical reports concerning the allergenicity of the whole food may not necessarily be a guide to the potential allergenicity of this protein extract in the future.

58. Investigations into fatal food reactions can be technically inadequate. The well-known case of Owen Carey’s fatal reaction was first reported to the FSA and local authority in November 2018 – 18 months after his death. In another case, Natasha Ednan-Laperouse’s death was first reported to the FSA in April 2018, i.e., 9 months later. Coroners do not always engage with local or national food authorities, which means opportunities for obtaining witness statements, food samples, and product data from suppliers are often missed.

59. Currently, there is limited feedback from clinicians to the food industry and regulators. More clinical trusts are going digital, so this data should be easier to capture, e.g., allergy diagnoses are recorded and shared across GPs and health trusts. There is no national system in place, so information from all clinical trusts cannot be accessed. In addition, there are issues with the clinical data and the systems are problematic. The current coding system does not allow the food to be logged. However, newer systems can permit foods to be entered, but not all food groups are currently included. Cross-sectional reporting does not work.

60. If this data is not being collected or published, then this information will not be available for the food allergenicity risk assessment.

4.1 Allergen Bioinformatics Session

61. Allergen bioinformatic tools (see Appendix 1) are used to conduct an in-silico assessment on the potential cross-reactivity between the protein(s) present in the novel food with existing known allergens.

62. There was a recognition that the available allergen bioinformatic tools are not currently adequate to apply with confidence in regulatory assessments. The lack of transparency regarding the systematic information for each allergen, and the variation in the inclusion criteria for each allergen in different databases, meant there is a question regarding the quality of the databases used in the development of these tools (Mazzucchelli et al., 2018; Radauer and Breiteneder, 2019). To address this issue, clinically relevant allergens should be used to benchmark the databases by checking the sequences and similarity to known allergenic proteins.

63. The current databases contain both food and inhalant allergens. In terms of the novel food allergenicity risk assessment, pollen proteins may or not be relevant. When genomic data rather than proteomic data is used, clarification on whether an open reading frame (ORF) results in protein expression and where in the plant this protein is expressed, is needed. This determination is relevant because a clinically relevant response requires consumption of the allergen.

64. At the time of the FSA allergenicity workshop, EFSA was conducting a systematic review of the clinical relevance of the current allergen bioinformatic tools. This report was not available for review by the FSA or the workshop participants prior to this meeting taking place.

65. Allergen bioinformatic tools employ a search engine that uses the FASTA local alignment algorithm (Pearson and Lipman, 1988) or the Basic Local Alignment Search Algorithm (BLAST) (Altschul et al., 1990). A sliding window analysis of the amino acid sequence from the novel food protein is used to assess the sequence homology with known allergens in the database. The default threshold, which was established by FAO/WHO (2001), is a > 35% sequence identity over a window of 80 amino acids when compared with known allergens. This approach was adopted by Codex Alimentarius (2003–2009) and EFSA (EFSA GMO Panel 2010, 2011). However, these algorithms were originally developed for searching for single proteins from genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and may not be adequate when applied to a large number of protein sequences (Harper et al., 2012). In addition, the sliding window is not as helpful in comparison to screening the whole protein sequencing for cross-reactivity.

66. The current default threshold can produce many false positives or produce a match with very rare food allergens. Under the current EFSA guidance (EFSA NDA Panel, 2016), this would lead to the next stage of allergenicity assessment, detection of specific IgE antibodies. Depending on the availability of sera from patients with clinically recognised food allergies, this stage of the assessment can be challenging when the bioinformatics indicates potential cross-reactivity with a minor allergen.

67. There are also reports of experimental IgE cross-reactivity between proteins which are below the threshold of > 35% sequence identity over a window of 80 amino acids (D’Avino et al., 2011; Guhsl et al., 2014; Dubiela et al., 2018).

68. Participants noted that the existing bioinformatic tools could be improved and provide better data than the current versions. Further work is needed to optimise the allergen databases.

69. Phylogenetic analysis is not currently used in the allergenicity risk assessment process. However, this approach could be used when the novel food comes from an organism which is closely related to a priority allergenic food, potentially reducing the amount of work needed in relation to multi-omic profiling. Phylogeny would also clearly identify an organism for which there is no history of use as a food. Further discussion would be needed to decide which tools should be used and how the information could be integrated into the allergenicity risk assessment process.

70. Other bioinformatic tools that identify cross-reactive allergens are currently being developed. 3D modelling of potentially allergenic proteins from novel foods, as well as 3D epitopes, could provide data that supports the observations from sequence homology analysis. In-silico human leukocyte antigen (HLA) binding could provide supporting information because HLA polymorphism has a possible role in the development of food allergy. However, further research is needed to clarify the role of HLA (Kostara et al., 2020).

71. In summary, participants recognised that the current allergen bioinformatic tools used for sequence homology could be improved. The key points were:

- Allergen bioinformatic tools cannot be used in isolation and should integrate other sources of information, e.g. history of use, targeted serum screening, clinically relevant studies, for example.

- The current and newly developed bioinformatic allergen tools should be validated against known allergens, non-allergens, and weak allergens.

- Existing and new databases should be targeted towards clinically relevant food allergens, for which information is currently available.

- The BLAST/FASTA algorithm should be changed to whole protein sequence similarity. The outcome from this test in terms of cross-reactivity should be identified. These steps could reduce the number of false positives detected and the need for further testing under the current EFSA guidelines.

- Consideration should be given to incorporating the taxonomic information into the allergenicity risk assessment process using phylogenetic tools.

- 3D modelling of epitopes and protein shapes/structures should be considered, but further work is needed to understand how these models have been developed, and each model would need validation.

- The FSA should consider funding research to clinically validate sequences.

4.2 In vitro Approaches Session

72. There is a recognition that bioinformatics analysis alone will not provide sufficient information to prospectively identify a potential food allergen. Evidence for a clinically relevant allergenic response in consumers typically follows exposure to the food for an extended period of time.

73. No single physicochemical property, such as protein solubility or thermal stability (i.e., heat treatment during food processing) can predict if a protein is allergenic (Costa et al., 2022a, b). Nonetheless, in conjunction with other information, this data can support the weight of evidence approach in allergenicity risk assessment

74. Food processing is also an important factor in the development of food allergenicity. Pea protein has widespread use in the production of meat-substitution products. However, case reports for pea allergy have become more frequent indicating that switching to a plant-based diet could harbour risks for certain individuals (Abu Risha et al., 2024).

75. There is no evidence that production processing can completely abolish the allergenicity of a protein in foods (Verhoeckx et al., 2015). Changes in the allergenicity have been noted, but this impact does not mitigate the risk sufficiently. Further research is needed to optimise these methods for different food types (Günal-Köroğlu et al., 2025).

76. When food processing results in ‘zero’ protein content, i.e., below the limit of detection, further allergenicity testing may not be needed. However, since novel foods are complex, any concerns about the potential presence of allergenic proteins should be investigated further.

77. Digestion tests should be considered as a part of the allergenicity risk assessment process because the size of peptides or proteins plays a key role in an IgE-mediated clinically relevant allergic response. Sensitisation and elicitation, according to the understanding of immunological mechanisms of food allergy types, require peptide fragments of a minimum size (FAO/WHO, 2024).

78. The nutritional assessment of a novel food usually includes an evaluation of the protein quality. The internationally recognised approach is the determination of the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) (FAO/WHO, 2013). As a novel food, this would typically involve an in vivo assay for determining the true ileal amino acid digestibility. In vitro assays have been also developed, but to date, none have international accreditation, e.g. OECD. Rather than perform two separate digestions studies for nutrition and allergenicity, consideration should be given to combining these two assays.

79. The IgE binding and cross-reactivity potential of a protein can be assessed using enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), immunoblotting, radioallergosorbent test (RAST), etc. Currently, the FAO/WHO guidance recommends 6 sera to demonstrate that a protein is a major allergen, with 95% confidence (FAO/WHO, 2001). This level of confidence was queried by participants. HLA recognition may also provide relevant information, but the role of this molecule in a clinically relevant allergic response remains unclear.

80. IgE binding does not indicate that a clinically relevant reaction will take place. The presence of specific IgE in plasma reflects sensitisation to a given allergen but does not predict that an allergic reaction will occur if the subject is exposed again to the same allergen. Roberts et al., (2016) report that 50% of patients with an allergen specific IgE concentration above the cut-off value do not have food allergy.

81. Therefore, a subsequent step might be needed to evaluate the clinical relevance of the in vitro IgE binding with ex vivo/in vitro functional testing strategies (Codex Alimentarius, 2003–2009; EFSA GMO Panel, 2010, 2011; Verhoeckx et al., 2016).

82. The final use of the protein could inform the allergenicity risk assessment strategy. A suggested pathway could involve reviewing the history of safe use by literature survey and taxonomy, determining the protein content, bioinformatic analysis, in vitro testing, and clinical testing (the ethnicity of the test subjects should be considered).

83. In summary, participants recognised that the current in vitro approaches could be refined. The key points were:

- Food processing does not significantly reduce the allergenic potential of protein in foods. However, ‘zero’ protein levels (below the limit of detection) in a novel food may not require further allergenicity testing.

- Although no single physicochemical property of the protein can predict allergenicity, in conjunction with other information, this data could support the weight of evidence approach in allergenicity risk assessment.

- Consideration should be given to combining the nutrition assessment of the digestibility of the novel food with the allergenicity assessment to reduce work.

- Analytical labs involved in testing and developing methods should have the appropriate accreditation. Protocols should be validated by recognised organisations or by conducting ring trials in different accredited laboratories.

- Investigate using NHS data in the allergenicity risk assessment from patient admissions and/or allergy clinics. Mandatory reporting for patients admitted with anaphylaxis is recommended.

4.3 Exposure and Threshold Session

84. Protein levels in the novel food should be determined as accurately as possible. FAO/WHO provides a summary of the analytical techniques available for accurately determining the protein content (Table 1, FAO/WHO, 2024). As each method has drawbacks, the suggested FAO/WHO strategy is to use more than one method, but with each chosen method based on different principles (e.g., amino acid analysis and Bradford assay).

85. Further work on allergenicity assessment of novel foods is planned to follow the outcome of this workshop. As part of this, the FSA will explore whether applicants need to provide justification on which analytical method they have used and how appropriate this is for the proteins present in the novel food.

86. An exposure assessment using this analytical data should be conducted to estimate the protein intake. Where an exposure assessment on the estimated protein intake is found to be lower than Reference dose (RfD) / 30, further allergenicity testing may not be necessary. The RfD/30 value appears to provide an adequate margin of safety for risk assessments (FAO/WHO, 2024).

87. Reference doses are based on whole foods and not individual proteins. The assessment should use the lowest reference dose for all allergens, which is 1 mg for mustard, or use proteins from similar families as a starting point. When low levels of protein detected, the severity of the allergic response in analogous proteins should be considered. If the protein is unknown and/or from a new source, the worst-case reference dose for priority allergens could be used.

88. When protein is present as a contaminant, e.g., from genetically modified microorganisms (GMM) used in the production of a novel food, an approach similar to the threshold of toxicological concern could be helpful.

89. The development of analytical tests and protocols for assessing allergenicity may be needed. Laboratories conducting this work should have the appropriate accreditation. Where possible, protocols should also be accredited by recognised organisations, e.g., OECD, or ring trials should be conducted in a few validated laboratories.

90. In summary, participants recognised that the following approaches could be useful in the allergenicity risk assessment. They key points were:

- Provide guidance for applicants concerning the appropriate strategies for determining the protein content of a novel food. FAO/WHO (2024) describes a recommended approach and limit of detection.

- Where protein exposure levels from the novel food are less than RfD/30, this may indicate that further allergenicity testing is not needed.

- Reference doses could still be used for protein(s) from foods that are unknown and/or from a new source.

- Analytical labs involved in testing and developing methods should have appropriate accreditation. Protocols should be validated by recognised organisations or by conducting ring trials in different accredited laboratories.

5. Round Table Discussion

91. Participants agreed that a flow chart should be developed that clarifies each step in the allergenicity risk assessment. Currently, there is relevant information scattered across FAO/WHO documents, EFSA publications and the published scientific literature (e.g., Verhoeckx et al., 2016) that could be integrated into a very direct workflow.

92. There is already a tiered approach to toxicology testing for foods, so this strategy could be adapted for allergenicity. There are questions that need to be addressed concerning the entry point for the allergenicity risk assessment, as well as the use of other information generated during the novel food safety assessment, e.g., nutritional assessment and protein digestibility.

93. A framework should be developed to clarify the triggers that lead to the next tier of allergenicity risk assessment. This should be based on a weight of evidence approach that is linked to the mechanism of the allergenic response. The information could also act as a trigger for a specific risk management strategy.

94. A list of validated methods and protocols should be provided for each stage of testing with further assistance from signposting relevant published guidance and papers.

95. An alternative approach to the flow chart strategy was discussed. This utilised a matrix system whereby results generated through tiered allergenicity testing, e.g., bioinformatics analysis, in vitro testing, etc, would be allocated a value. The cumulative testing score would inform on the level of concern for the novel food and help to inform the risk management strategy.

96. An important query was raised regarding Article 4 of assimilated Commission Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 which concerns the determination of the status of a novel food. When a food is found to be not novel due to a prior history of consumption within the UK or EU, no authorisation is required. Under these circumstances potentially allergenic foods would not undergo any form of allergenicity risk assessment prior to marketing. This in turn would mean that the FSA would have no opportunity to consider any appropriate risk management measures for this food.

97. Participants also discussed several other related topics linked to the allergenicity risk assessment which are summarised below.

98. For sequence homology, the current threshold of concern is a > 35% sequence identity over a window of 80 amino acids (FAO/WHO, 2001), which triggers further studies under the current guidance. The significance of this threshold value and whether this realistically identifies a food allergen was questioned. Increasing the threshold was suggested, but no definitive value was identified. There was also uncertainty over what influence the degree of sequence homology should have over the next steps in the allergenicity risk assessment.

99. The NHS has access to clinical data that could inform on both risk assessment and risk management of potential allergens in a novel food. However, there was a recognition that there is a problem with the national clinical database infrastructure, as well as the collection of relevant data concerning clinically relevant allergies. Further analysis and collaboration between FSA and DHSC are needed to address how this data could be made available and incorporated into the allergenicity risk assessment. There was also a recommendation that the mandatory reporting of patients admitted with anaphylaxis should be considered.

100. The use of post-market monitoring could potentially be used to track what is happening in the real world in terms of allergic responses in consumers of novel foods. This strategy is not currently used in allergenicity risk assessment, but there is research in this area. The FSA currently funds the UK Fatal Anaphylaxis Register which could be a source of information for the allergenicity risk assessment for novel foods. Further investigation would be needed to decide how much emphasis should be placed on this data and how should this information be collected.

101. Cats, dogs, and horses reportedly develop food allergies like humans (Pali-Scholl et al., 2017). There is currently little information about the specific molecules that are responsible for the allergic reactions seen in these animals; however, current reports indicate the development of food allergies are similar. Potentially, veterinary reports concerning animal feed may provide supporting information that could be utilised the allergenicity risk assessment. Participants recognised that more in-depth research would be needed to evaluate this approach.

102. Nutritional information, including amino acid content and protein quality, is a key part of the overall novel food safety assessment. The digestible indispensable amino acid score (DIAAS) is an internationally recognised method for determining the quality of protein. Since this method requires in vivo digestibility data, further work on adapting the DIAAS protocol should be considered.

103. IgE binding and cross-reactivity testing is the next tier of the current allergenicity assessment when bioinformatic analysis of the novel food exceeds the threshold of concern. The FAO/WHO guidance provides recommendations on the number of sera samples that should be tested for major and minor allergens (FAO/WHO, 2001). However, applicants encounter difficulties sourcing sufficient samples to conduct serum screening, particularly for minor allergens. Participants recognised that applicants need further assistance in this area.

6. Draft Workflow for further guidance

104. Based on the feedback from participants during the breakout sessions, and the subsequent round table discussion, a draft workflow for further guidance to support applicants during the novel food allergenicity risk assessment process was developed (Diagram 1). Additional information from relevant FAO publications, EFSA reports, and published peer review papers was also incorporated into this diagram.

105. The diagram is intended to be used as a starting point for the ACNFP for consideration during their revision of the guidelines for the novel food allergenicity risk assessment.

7. Conclusion

106. The FSA hosted an Allergenicity Workshop in February 2024 following a request from the ACNFP to consider revising the guidelines and developing a clearer framework for the allergenicity risk assessment process.

107. Food allergy experts from a range of perspectives were brought together in order to gather their viewpoints on the current and future approaches in allergenicity risk assessment. Participants worked in small breakout groups to review key topics on food allergenicity and were then invited to take part in a round table discussion to review their findings and make recommendations.

108. Based on these discussions, and other supporting sources of information (FAO publications; EFSA reports; published peer review papers) a draft workflow was developed. This template will be used as a starting point to revise the guidelines for the novel food allergenicity risk assessment.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to the following participants: Dr Camilla Alexander-White (ACNFP Chair), Professor Clare Mills (ACNFP), Ms Rebecca McKenzie (ACNFP), Professor Hans Verhagen (ACNFP), Dr Elizabeth Lund (ACNFP), Ms Alison Austin (ACNFP), Dr Rene Crevel (external consultant), Dr Paul Turner (Imperial College), Dr Pina Rotiroti (University College London Hospital), Dr Kate Grimshaw (Manchester Metropolitan University), Ms Rachael Ward (Exponent), Mrs Hazel Gowland (Allergy UK), Baroness Alicia Kennedy (The Natasha Allergy Research Foundation), Dr Rebecca Knibb (Aston University), Dr Chrissie Jones (University of Southampton), Professor Julie Lovegrove (University of Reading), Dr Kitty Verhoeckx (UMC Utrecht).

FSA Support Staff: Matt Hall, Lucy Thursfield, Jessica Cairo, Victoria Balch.

Abbreviations

|

Abbreviation |

Definition |

|

ACNFP |

Advisory Committee for Novel Foods and Processes |

|

BLAST |

Basic Local Alignment Search Algorithm |

|

CRO |

Clinical Research Organisation |

|

DBPCFC |

Double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge |

|

DIAAS |

Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score |

|

DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

|

EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

|

ELISA |

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay |

|

FAO |

Food and Agricultural Organization |

|

FASTA |

Fast-A algorithm |

|

FSA |

Food Standards Agency |

|

GI |

Gastro-intestinal |

|

GM |

Genetically modified |

|

GMM |

Genetically modified microorganism |

|

GMO |

Genetically modified organism |

|

HLA |

Human leukocyte antigens |

|

IgA |

Immunoglobulin A |

|

IgE |

Immunoglobulin E |

|

IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

|

MHCII |

Major Histocompatibility Complex II |

|

ORF |

Open reading frame |

|

PAFA |

Patterns and Prevalence of Adult Food Allergy |

|

mRNA |

Messenger ribonucleic acid |

|

RAST |

Radioallergosorbent test |

|

RfD |

Reference dose for priority allergenic foods |

References

Abu Risha M, Rick EM, Plum M, Jappe U, 2024. Legume Allergens Pea, Chickpea, Lentil, Lupine and Beyond. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports Sep;24(9) pp 527-548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-024-01165-7

Akkerdaas J, Totis M, Barnett B, Bell E, Davis T, Edrington T, Glenn K, Graser G, Herman R, Knulst A, Ladics G, McClain S, Poulsen LK, Ranjan R, Rascle J-B, Serrano H, Speijer D, Wang R, Pereira Mouries L, Capt A and van Ree R, 2018. Protease resistance of food proteins: a mixed picture for predicting allergenicity but a useful tool for assessing exposure. Clinical and Translational Allergy, 8, 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-018-0216-9

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW and Lipman DJ, 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology, 215, pp 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999

Ballardini N, Nopp A, Hamsten C, Vetander M, Melén E, Nilsson C, Ollert M, Flohr C, Kuehn A, van Hage M, 2017. Anaphylactic Reactions to Novel Foods: Case Report of a Child with Severe Crocodile Meat Allergy. Pediatrics. Apr;139(4) e20161404. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1404

Brough HA, Caubet JC, Mazon A, Haddad D, Bergmann MM, Wassenberg J, Panetta V, Gourgey R, Radulovic S, Nieto M, Santos AF, Nieto A, Lack G, Eigenmann PA, 2020. Defining challenge-proven coexistent nut and sesame seed allergy: A prospective multicentre European study. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Apr;145(4) pp 1231-1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2019.09.036

Buka RJ, Crossman RJ, Melchior CL, Huissoon AP, Hackett S, Dorrian S, Cooke MW, Krishna MT, 2015. Anaphylaxis and ethnicity: higher incidence in British South Asians. Allergy Dec;70(12) pp 1580-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12702

Cherkaoui M, Le Corre E, Ahmat-Sougoudi A, Perrin E, Solé-Jamault V, Rabesona H, Denery-Papini S, Morisset M, Rogniaux H, Dijk W, 2025. Exploring the molecular modifications and allergenicity of the egg white protein matrix during boiling. Food Chemistry Aug 15;483 144304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.144304

Costa J, Villa C, Verhoeckx K, Cirkovic-Velickovic T, Schrama D, Roncada P, Rodrigues PM, Piras C, Martín-Pedraza L, Monaci L, Molina E, Mazzucchelli G, Mafra I, Lupi R, Lozano-Ojalvo D, Larré C, Klueber J, Gelencser E, Bueno-Diaz C, Diaz-Perales A, Benedé S, Bavaro SL, Kuehn A, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, Holzhauser T., 2022. Are Physicochemical Properties Shaping the Allergenic Potency of Animal Allergens? Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology Feb;62(1) pp 1-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-020-08826-1

Costa J, Bavaro SL, Benedé S, Diaz-Perales A, Bueno-Diaz C, Gelencser E, Klueber J, Larré C, Lozano-Ojalvo D, Lupi R, Mafra I, Mazzucchelli G, Molina E, Monaci L, Martín-Pedraza L, Piras C, Rodrigues PM, Roncada P, Schrama D, Cirkovic-Velickovic T, Verhoeckx K, Villa C, Kuehn A, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, Holzhauser T., 2022. Are Physicochemical Properties Shaping the Allergenic Potency of Plant Allergens? Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology Feb;62(1) pp 37-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-020-08810-9

Crevel RWR, Verhoeckx K, Bøgh KL, Buck N, Chentouf A, Flanagan A, Galano M, Garthoff JA, Hazebrouck S, Yarham R, Borja G, Houben G, 2024. Allergenicity assessment of new or modified protein-containing food sources and ingredients. Food and Chemical Toxicology 189 114766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2024.114766

D’Avino R, Bernardi ML, Wallner M, Palazzo P, Camardella L, Tuppo L, Alessandri C, Breiteneder H, Ferreira F, Ciardiello MA and Mari A, 2011. Kiwifruit Act d 11 is the first member of the ripening-related protein family identified as an allergen. Allergy, 66, pp 870–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02555.x

Datema MR, Zuidmeer-Jongejan L, Asero R, Barreales L, Belohlavkova S, de Blay F, Bures P, Clausen M, Dubakiene R, Gislason D, Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz M, Kowalski ML, Knulst AC, Kralimarkova T, Le TM, Lovegrove A, Marsh J, Papadopoulos NG, Popov T, Del Prado N, Purohit A, Reese G, Reig I, Seneviratne SL, Sinaniotis A, Versteeg SA, Vieths S, Zwinderman AH, Mills C, Lidholm J, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, Fernández-Rivas M, Ballmer-Weber B, van Ree R, 2015. Hazelnut allergy across Europe dissected molecularly: A EuroPrevall outpatient clinic survey. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Aug;136(2) pp 382-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1949

Dubiela P, Kabasser S, Smargiasso N, Geiselhart S, Bublin M, Hafner C, Mazzucchelli G and Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, 2018. Jug r 6 is the allergenic vicilin present in walnut responsible for IgE cross-reactivities to other tree nuts and seeds. Scientific Reports, 8, 11366. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-29656-4

EFSA GMO Panel (Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms), 2006. Guidance document for the risk assessment of genetically modified plants and derived food and feed by the Scientific Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO) - including draft document updated in 2008. EFSA Journal 4(4) 99, [105 pp]. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2006.99

EFSA GMO Panel (EFSA Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms), 2010. Scientific Opinion on the assessment of allergenicity of GM plants and microorganisms and derived food and feed. EFSA Journal 8(7) 1700, [168pp]. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1700

EFSA GMO Panel (EFSA Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms), 2011. Scientific Opinion on guidance for risk assessment of food and feed from genetically modified plants. EFSA Journal 9(5) 2150, [37 pp]. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2150

EFSA GMO Panel (EFSA Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms), 2017. Guidance on allergenicity assessment of genetically modified plants. EFSA Journal 15(5): 4862, [49 pp]. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4862

EFSA GMO Panel (EFSA Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms), 2021a. Statement on in vitro protein digestibility tests in allergenicity and protein safety assessment of genetically modified plants. EFSA Journal 19(1):6350, [16 pp]. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2021.6350

EFSA GMO Panel (EFSA Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms), 2021b. Workshop on allergenicity assessment – prediction. EFSA Supporting publication EN-6826. [16 pp]. https://doi.org/10.2903/sp.efsa.2021.EN-6826

EFSA GMO Panel (FSA Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms), 2022. Scientific Opinion on development needs for the allergenicity and protein safety assessment of food and feed products derived from biotechnology. EFSA Journal 20(1) 7044, [38pp]. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2022.7044

EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies), 2016. Guidance on the preparation and presentation of an application for authorisation of a novel food in the context of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 (Question no: EFSA-Q-2014-00216, adopted: 21 September 2016). EFSA Journal, 14, 4594 (24pp). https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4594

EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens), 2023. Scientific Opinion on the nutritional safety and suitability of a specific protein hydrolysate derived from a whey protein concentrate and used in an infant formula and follow-on formula manufactured from hydrolysed protein by Friesland Campina Nederland B.V. EFSA Journal 21(7):8063, [13 pp.] https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2023.8063

FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture organisation of the United Nations/World Health Organisation), 2001. Evaluation of Allergenicity of Genetically Modified Foods. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Allergenicity of Foods Derived from Biotechnology, Rome / Italy. 22-25 January: pp. 1-18. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/publications/evaluation-of-allergenicity.pdf

FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture organisation of the United Nations/World Health Organisation), 2013. Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition. Report of an FAQ Expert Consultation. FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 92 pp 1-66. https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i3124e

FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture organisation of the United Nations/World Health Organisation), 2022a. Risk Assessment of Food Allergens. Part 1 – Review and validation of Codex Alimentarius priority allergen list through risk assessment. Meeting Report. Food Safety and Quality Series No. 14. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb9070en

FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture organisation of the United Nations/World Health Organisation), 2022b. Risk assessment of food allergens – Part 2: Review and establish threshold levels in foods for the priority allergens. Meeting Report. Food Safety and Quality Series No. 15. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc2946en

FAO/WHO (Food and Agriculture organisation of the United Nations/World Health Organisation), 2024. Risk assessment of food allergens – Part 4: Establishing exemptions from mandatory declaration for priority food allergens. Food Safety and Quality Series, No. 17. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc9554en

Foo ACY and Mueller GA, 2021. Abundance and stability as common properties of allergens. Frontiers Allergy, 2, 769728. https://doi.org/10.3389/falgy.2021.769728

Fox AT, Kaymakcalan H, Perkin M, du Toit G, Lack G. Changes in peanut allergy prevalence in different ethnic groups in 2 time periods, 2015. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Feb;135(2) pp 580-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.022

Francis OL, Wang KY, Kim EH, Moran TP, 2020. Common food allergens and cross-reactivity. Journal of Food Allergy Sep 1;2(1) pp 17-21. https://doi.org/10.2500/jfa.2020.2.200020

Gantulga P, Lee J, Jeong K, Jeon SA, Lee S, 2024. Variation in the Allergenicity of Scrambled, Boiled, Short-Baked and Long-Baked Egg White Proteins. Journal of Korean Medical Science. Feb 19;39(6):e54. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2024.39.e54

Guhsl EE, Hofstetter G, Hemmer W, Ebner C, Vieths S, Vogel L, Breiteneder H and Radauer C, 2014. Vig r 6, the cytokinin-specific binding protein from mung bean (Vigna radiata) sprouts, cross-reacts with Bet v 1-related allergens and binds IgE from birch pollen allergic patients’ sera. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 58, pp 625–634. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201300153

Günal-Köroğlu D, Karabulut G, Ozkan G, Yılmaz H, Gültekin-Subaşı B, Capanoglu E., 2025. Allergenicity of Alternative Proteins: Reduction Mechanisms and Processing Strategies. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry Apr 2;73(13) pp 7522-7546. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5c00948

Harper B, McClain S and Ganko EW, 2012. Interpreting the biological relevance of bioinformatic analyses with T-DNA sequence for protein allergenicity. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology, 63, 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2012.05.014

Jutel M, Agache I, Zemelka-Wiacek M, Akdis M, Chivato T, Del Giacco S, Gajdanowicz P, Gracia IE, Klimek L, Lauerma A, Ollert M, O'Mahony L, Schwarze J, Shamji MH, Skypala I, Palomares O, Pfaar O, Torres MJ, Bernstein JA, Cruz AA, Durham SR, Galli SJ, Gómez RM, Guttman-Yassky E, Haahtela T, Holgate ST, Izuhara K, Kabashima K, Larenas-Linnemann DE, von Mutius E, Nadeau KC, Pawankar R, Platts-Mills TAE, Sicherer SH, Park HS, Vieths S, Wong G, Zhang L, Bilò MB, Akdis CA, 2023. Nomenclature of allergic diseases and hypersensitivity reactions: Adapted to modern needs: An EAACI position paper. Allergy Nov;78(11) pp 2851-2874. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.15889

Knox J and Jarvis D, 2003. The European Community Respiratory Health Survey II. European Respiratory Journal 21(3) pp556-560. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.03.00094802

Kostara M, Chondrou V, Sgourou A, Douros K, Tsabouri S. HLA Polymorphisms and Food Allergy Predisposition. Journal of Paediatric Genetics. 2020 Jun;9(2) pp 77-86. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1708521

Liu EG, Tan J, Munoz JS, Shabanova V, Eisenbarth SC, Leeds S, 2024. Food Matrix Composition Affects the Allergenicity of Baked Egg Products. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Practice Aug;12(8) pp 2111-2117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2024.04.032

Luyt D, Ball H, Makwana N, Green MR, Bravin K, Nasser SM, Clark AT, 2014. Standards of Care Committee (SOCC) of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI). BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow's milk allergy. Clinical and Experimental Allergy 44(5) pp 642-72. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.12302

Lyons SA, Burney PGJ, Ballmer-Weber BK, Fernandez-Rivas M, Barreales L, Clausen M, Dubakiene R, Fernandez-Perez C, Fritsche P, Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz M, Kowalski ML, Kralimarkova T, Kummeling I, Mustakov TB, Lebens AFM, Van Os-Medendorp H, Papadopoulos NG, Popov TA, Sakellariou A, Welsing PMJ, Potts J, Mills ENC, Van Ree R, Knulst AC and Le TM, 2019. Food allergy in adults: substantial variation in prevalence and causative foods across Europe. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Practice, 7, pp 1920-1928 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.02.044

Mazzucchelli G, Holzhauser T, Cirkovic Velickovic T, Diaz-Perales A, Molina E, Roncada P, Rodrigues P, Verhoeckx K and Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, 2018. Current (food) allergenic risk assessment: is it fit for novel foods? Status quo and identification of gaps. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 62, 1700278. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201700278

Pearson WR and Lipman DJ, 1988. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 85, pp 2444–2448. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444

Pali-Schöll I, De Lucia M, Jackson H, Janda J, Mueller RS, Jensen-Jarolim E. Comparing immediate-type food allergy in humans and companion animals—revealing unmet needs. Allergy. 2017; 72: pp 1643–1656. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13179

Perkin MR, Logan K, Tseng A, Raji B, Ayis S, Peacock J, Brough H, Marrs T, Radulovic S, Craven J, Flohr C, Lack G; EAT Study Team, 2016. Randomized Trial of Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Breast-Fed Infants. New England Journal of Medicine May 5;374(18) pp 1733-43. https//doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1514210

Perkin MR, Bahnson HT, Logan K, Marrs T, Radulovic S, Knibb R, Craven J, Flohr C, Mills EN, Versteeg SA, van Ree R, Lack G; Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study team, 2019. Factors influencing adherence in a trial of early introduction of allergenic food. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Dec;144(6) pp 1595-1605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.046

Pilolli R, Gadaleta A, Mamone G, Nigro D, De Angelis E, Montemurro N and Monaci L, 2019. Scouting for naturally low-toxicity wheat genotypes by a multidisciplinary approach. Scientific Reports, 9, 1646. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36845-8

Puche L, López-Sánchez D, Blanca-Lopez N, Somoza-Alvarez MK, Diaz EH, Diaz-Perales A, Canto MG, Blanca M, 2018. Peach pollen sensitisation is highly prevalent in areas of great extension of peach tree cultivar. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Volume 141, Issue 2, AB31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.099

Radauer C and Breiteneder H, 2019. Allergen databases – a critical evaluation. Allergy, 74, 2057–2060. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13841

Roberts G, Ollert M, Aalberse R, Austin M, Custovic A, DunnGalvin A, Eigenmann PA, Fassio F, Grattan C, Hellings P, Hourihane J, Knol E, Muraro A, Papadopoulos N, Santos AF, Schnadt S, Tzeli K. A new framework for the interpretation of IgE sensitization tests. Allergy. 2016 Nov;71(11) pp1540-1551. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.12939

Shan L, Molberg Ø, Parrot I, Hausch F, Filiz F, Gray GM, Sollid LM and Khosla C, 2002. Structural basis for gluten intolerance in celiac sprue. Science, 297, pp 2275–2279. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1074129

Sicherer SH and Sampson HA, 2014. Food allergy: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 133(2) pp 291-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.020

Stiefel G, Anagnostou K, Boyle RJ, Brathwaite N, Ewan P, Fox AT, Huber P, Luyt D, Till SJ, Venter C, Clark AT, 2017. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of peanut and tree nut allergy. Clinical & Experimental Allergy, 47, pp 719–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.12957

Turner PJ, Andoh-Kesson E, Baker S, Baracaia A, Barfield A, Barnett J, Brunas K, Chan CH, Cochrane S, Cowan K, Feeney M, Flanagan S, Fox AT, George L, Gowland MH, Heeley C, Kimber I, Knibb R, Langford K, Mackie A, McLachlan T, Regent L, Ridd M, Roberts G, Rogers A, Scadding G, Stoneham S, Thomson D, Urwin H, Venter C, Walker M, Ward R, Yarham RAR, Young M, O'Brien J, 2021. Identifying key priorities for research to protect the consumer with food hypersensitivity: A UK Food Standards Agency Priority Setting Exercise. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. Oct;51(10) pp 1322-1330. https://doi.org/10.1111/cea.13983

University of Manchester, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, University of Southampton, Amsterdam University Medical Centre, & Isle of Wight NHS Trust, 2024. Patterns and Prevalence of Adult Food Allergy. FSA Research and Science [102 pp]. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.q1122

Verhoeckx KCM, Vissers YM, Baumert JL, Faludi R, Feys M, Flanagan S, Herouet-Guicheney C, Holzhauser T, Shimojo R, van der Bolt N, Wichers H, Kimber I., 2015. Food processing and allergenicity. Food and Chemical Toxicology. Jun;80 pp 223-240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2015.03.005

Verhoeckx K, Broekman H, Knulst A, Houben G, 2016. Allergenicity assessment strategy for novel food proteins and protein sources. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 79 pp 118-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.03.016

Vriz R, Moreno FJ, Koning F and Fernandez A, 2021. Ranking of immunodominant epitopes in celiac disease: Identification of reliable parameters for the safety assessment of innovative food proteins. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 157, 112584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2021.112584

Warren CM, Bartell TR, 2024. Sociodemographic inequities in food allergy: Insights on food allergy from birth cohorts. Paediatric Allergy and Immunology. Apr;35(4): e14125. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.14125

Weinberger T and Sicherer S, 2018. Current perspectives on tree nut allergy: a review. Journal of Asthma and Allergy, 11, pp 41–51. https://doi.org/10.2147/JAA.S141636

Xu Y, Ahmed I, Zhao Z, Lv L, 2024. A comprehensive review on glycation and its potential application to reduce food allergenicity. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 64(33) pp 12184-12206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2023.2248510

Zhang S, Sicherer S, Berin MC, Agyemang A. Pathophysiology of Non-IgE-Mediated Food Allergy. Immunotargets and Therapy. 2021 Dec 29; 10 pp 431-446. https://doi.org/10.2147/ITT.S284821

Appendix 1: Questions and summary of responses from each breakout session

Breakout Group 1: Allergen Bioinformatics

Question: Is the current use of bioinformatic tools providing the best data to inform the allergenicity assessment? If not, how should they be adapted in light of scientific developments?

- Tools need updating to account for protein shape.

- Inadequate standard as what should be included in bioinformatic database, i.e., clinical relevance; drives potential false positives which take time/resources to explain.

- Bioinformatic results on secondary amino acid sequences do not consider tertiary structure or glycosylation impact on homology similarity to known allergens – best data to compare with known allergens.

- Only useful for known allergens.

- No because giving too many false positives and negatives.

- If bioinformatic tools are not fit for purpose, why use them?

Question: What further information could additional use of bioinformatic tools provide to risk assessors?

- Relevance? Is there going to be a cross-reactivity issue?

- CROs need to be set-up to generate data.

- Taxonomic/phylogenetic relationships can drive assessment.

- Sequence alone is not as useful as topology.

- Use related proteins, e.g., legumes, crustaceans, of known allergens – do we use epitope or whole protein?

Question: What dataset(s)/tool(s) should the applicant use? What cut-off for amino acid homology should be used? How should this information be used?

- Complete database required, but where is data coming from? No ‘hits’ may mean no dat.

- Use CRO knowledge to focus on what to look for?

- Update database – major and minor allergens – prevalence – clinical relevance – severity – delete fragments – only perform further studies when protein is homologue to clinically relevant protein.

- DBPCFC for those who are allergic and interested in novel food.

- Describe the problem – describe the need for a solution – sell it to senior FSA, then other interested parties – appeal to variety of motivations.

Question: Are there any approaches are not being used?

- Look at HLA binding and tertiary modelling – could be beneficial especially in adverse outcome pathway.

- Expert driven ‘black box’ algorithms currently using 1996 technology.

- Scientific information on topology and glycosylation patterns – information is not available to CROs.

- Quality standards for data for inclusion of sequences in bioinformatic databases – clinical relevance; weight/degree of potency.

- Food challenge data.

- Consideration of shape of epitope during processing.

- In-silico database based on allergen/non-allergen. What is their value if they are not correct?

Question: Based on the available tools, what would be the preferred approach for assessing the allergenicity of foods?

- Small peptides may present an immunological risk or allergenicity potential. Would not use bioinformatic tools for this scenario – need to confirm reactivity potential.

- Stepwise approach – phylogenetics tree – look at clinical anaphylaxis data for related proteins – where still considered, immunoblot with pooled allergic sera.

- Phylogenetic tree – clinical testing.